Home » Resources » The War on the War on Christmas – Or Something Like That

The War on the War on Christmas – Or Something Like That

- December 20, 2023

- Written by cheni vega

Happy Debate-about-the-Debate-about-How-to-Express-Seasons-Greetings Season! Yes, it’s time to renew one of America’s greatest meta rituals, talking about how we talk about the Festivus season.

Of course, we wouldn’t have this meta-tradition were it not for the tradition it builds on. Most of the discussion about the War on Christmas traces its history back to Bill O’Reilly’s 2004 “Christmas under Siege” episode of The O’Reilly Factor. But that timeline doesn’t do the War on Christmas justice; the John Birch Society had lamented a lack of Christmas spirit in the 1950s and Henry Ford did the same in the 1920s. The scapegoats reflect the particular era’s objects of right-wing paranoia – today’s “secular humanist elite” was preceded by “the UN” and “The Jews” respectively – but the general tune was the same: a nefarious conspiracy was plotting against Christmas!

The crackpots were right in a way, though…there really was a War on Christmas at one point. In fact, it goes all the way back to Plymouth Rock.

The War on Christmas Is Almost as Old as Thanksgiving

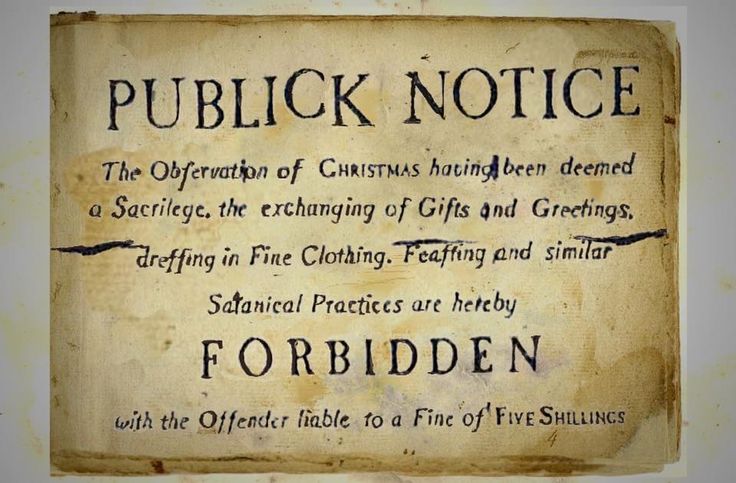

Unfortunately, for the self-proclaimed Defenders of Christmas, it was their heroes who waged America’s first battle against the yuletide season. That’s right, the Pilgrims discouraged Christmas celebrations and the Massachusetts Bay Colony actually banned them in Boston in 1659. Puritans were suspicious of Christmas’s pagan Roman roots and Catholic overtones, and absolutely loathed the feasting, revelry, and general merriment that went along with it (it’s not for nothing that H.L. Mencken defined Puritanism as the haunting fear that someone, somewhere might be happy). So, when John Winthrop talked about America as a shining city on a hill, the glow he saw wasn’t coming from any lights that had been strung up.

American Christmas – An Inclusive Tradition

But while the Puritans and their theological heirs avoided celebrating Christmas until after the Civil War, the rest of the country was busy building today’s holiday traditions by mashing a bunch of culturally specific ones together in typical American fashion. “Old Saint Nick” is just one example. Saint Nicholas was a 4th-century Greek bishop who lived in the southern part of modern-day Turkey. He was the patron saint of children and gift-giving, which led to much of Europe exchanging gifts on the night before his Name Day. That day, December 6, was close enough to Christmas that the gift-giving migrated on the American calendar to the bigger celebration.

The Dutch name for Saint Nicholas – Sinterklaas – became Santa Claus thanks to Washington Irving. His alter ego of “Kris Kringle” came from the German Chistkindl, the traditional gift-giver in German-speaking Europe. Dutch and German names notwithstanding, Santa came to resemble the English Father Christmas and Dickens’s Ghost of Christmas Present during the 1800s. All of that had to happen before the New York Sun could say “Yes, Virginia, There Is a Santa Claus”. And Santa’s still evolving to fit the needs of various communities…just look at Honolulu Hale, where Shaka Santa (and his wife Tūtū Mel) have wished passers-by a Mele Kalikimaka for the past few decades.

Christmas became a federal holiday in 1870, so it should be no surprise that non-Christian Americans developed Christmas – and other holiday – traditions of their own. Late 19th Century Jewish New Yorkers faced a dilemma if they wanted to eat out on Christmas, when most restaurants were closed; the proximity of the Lower East Side Chinatown provided a solution and Jewish people have enjoyed Chinese food on Christmas ever since. And since Hanukkah tends to fall between Thanksgiving and Christmas, it was easy to wrap it into the general holiday season. Kwanzaa was created by Maulana Karenga in the 1960s. He intended it as a pan-African alternative to Christmas…but because it was to be an alternative, it takes at the same time as well.

The observance of American – or Western – Christmas has even spread to places with different or no indigenous Christmas traditions. In Japan, for example, it’s become a tradition to eat Kentucky Fried Chicken on Christmas Day (thanks in no small part to effective advertising!) And in July, the Ukrainian government passed a law moving Christmas to December 25 rather than the day specified by the Russian Orthodox calendar.

Implications for Marketers

OK, that’s a lot to unpack. The point is, arguing over the “right” way to celebrate the holiday season is as old a holiday tradition as any other Americans have. But it says something that the same folks who wanted to ban it 400 years ago now want to dictate how everybody celebrates it. We say, don’t let them get Christmas to themselves. It’s as OK for brands to say “Merry Christmas”, “Feliz Navidad”, or any derivation thereof as it is to say “Happy Holidays” and “Season’s Greetings”. In fact, it’s kind of important to say them all. And it’s not just because about 90% of Americans celebrate Christmas in some way shape or form, and people like to feel seen. It’s because saying it will deprive the idea of a “War on Christmas” of oxygen. The Bill O’Reillys and their ilk will keep saying the war exists, of course. But it’ll be tough to take them seriously when the idea gets mugged by reality. Christmas belongs to all of us.

We at PACO will be delighted to help you navigate the Christmas/holiday wars in a way that’s both true to your brand and inclusive to everyone you want to celebrate with. If you’d like to work with us please contact us here.

In the meantime, please enjoy one of many Christmas classics written or performed by a non-Christian American. And whatever your cultural and/or religious tradition, Season’s Greetings!